Enhancing FHIR for Social Services, published by SDOH. This guide is not an authorized publication; it is the continuous build for version 0.1.0 built by the FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) CI Build. This version is based on the current content of https://github.com/HL7/efss/ and changes regularly. See the Directory of published versions

TANF Use Case 3

- Whole Person Care TANF - Use Case

- Problem Statement:

- Eligibility Requirements for TANF (In-General):

- Scenario 0 – TANF (Non-Tribal) – Current State with HL7 FHIR Patient Focus Only:

- Scenario 1 – TANF:

- Scenario 2 – TANF:

- Scenario 3 – Tribal TANF:

- Scenario 4 – Tribal TANF:

- Existing Data Models from the Family Self-Sufficiency Data Center (FSSDC):

Whole Person Care TANF - Use Case

Problem Statement:

Navigating the intricacies of TANF, both within standard and tribal contexts, presents beneficiaries with challenges rooted in understanding eligibility criteria, meeting necessary requirements, and accessing appropriate resources. As they transition through TANF’s phases, a wealth of socio-economic and health-related data emerges. Yet, this data remains siloed, limiting its potential in informing and enhancing holistic care approaches.

The integration of TANF data into broader healthcare systems using FHIR standards can bridge this gap, ensuring beneficiaries receive comprehensive support that considers their socio-economic realities, while healthcare providers gain a more rounded understanding of their patients’ lives and challenges.

In the realm of health informatics, much of the focus historically falls on the “Patient” status, a designated when someone seeks medical care. The HL7 FHIR standard, as an embodiment of this focus, gives primacy to the “Patient Resource”. This approach makes practical sense in a healthcare-centric context; after all, healthcare providers interact with patients. However, when we expand our perspective to encompass social care, this patient-centric model presents limitations.

Every individual, before becoming a patient in the healthcare system, exists first and foremost as a “Person”. This concept transcends the boundaries of medical care to encompass the holistic experience of an individual in society. Especially in contexts like social care, where individuals often interface with systems not as medical patients but as citizens, family members, or community participants, the importance of the “Person” is paramount. TANF, as a social care initiative, interacts with people based on their societal roles, needs, and circumstances, not merely their health status.

The distinction becomes crucial when we consider the paradigm of “Whole Person Care”. This model acknowledges that an individual’s health is deeply intertwined with their social, economic, and environmental context. By relegating “Person Resource” to an afterthought, the current HL7 FHIR standard might inadvertently be promoting a fragmented view of care. To realize truly integrated and person-centered care, it’s vital that informatics standards recognize the centrality of the “Person” and structure data exchange mechanisms around it.

Reimagining the HL7 FHIR framework with the “Person” at its core is not merely a semantic shift; it’s a fundamental reorientation. It signifies the move from episodic, fragmented care to a model where an individual’s interactions with both the healthcare and social care systems are seen as interconnected parts of a continuum. In the case of TANF, for instance, understanding an individual’s broader life context, family dynamics, educational background, and employment status is crucial, if not more so, than their medical history.

In conclusion, as the lines between healthcare and social care blur, and as the call for integrated, whole-person care grows louder, there is an urgent need to re-evaluate and adapt our informatics standards. By elevating the “Person Resource” to its rightful place of prominence in the HL7 FHIR standard, we can lay the foundation for a more holistic, integrated, and person-centered approach to care — one that truly addresses the complexities and interconnections of modern healthcare and social care.

Eligibility Requirements for TANF (In-General):

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) is a U.S. federal assistance program. While the program is federally funded, each state administers its own TANF program, establishes its own eligibility criteria, and determines the type and amount of assistance payments.

As a result, the specific requirements can vary from state to state.

However, there are general eligibility requirements that apply across states:

- Income Limits:

- Applicants must have a low or very low income.

- Each state has its own set income thresholds based on family size.

- Both earned (like wages) and unearned (like unemployment benefits) income are considered.

- Asset Limits:

- Some states set asset limits, such as the value of vehicles, bank account balances, or properties, excluding the applicant’s primary home.

- U.S. Citizenship or Eligible Non-Citizen Status:

- Applicants must be U.S. citizens or specific categories of eligible non-citizens, such as lawful permanent residents.

- Non-citizens might have a waiting period before they can apply.

- Children in Household:

- TANF is primarily for families with children under 18.

- The child might be required to live in the home of a parent or a close relative.

- In some states, pregnant women in their last trimester can also qualify.

- Cooperation with Child Support Services:

- If a parent applies for TANF benefits for a child but is not cooperating with child support services to obtain support from the other parent, they might be disqualified.

- Work Requirements:

- Adults must participate in work or training activities for a certain number of hours per week, unless they are exempt (e.g., due to being pregnant or having a young child).

- States have flexibility in defining these activities, which can include actual employment, job search, community service, or vocational training.

- Time Limits:

- Families can receive TANF for a maximum of 60 months (5 years) in their lifetime, although some states have shorter limits.

- States can exempt up to 20% of their caseload from this limit if they face hardships.

- Social Security Number:

- Applicants are required to provide or apply for a Social Security Number (SSN) for each member of the family seeking assistance.

- Immunization Requirements:

- Some states require that children be immunized to be eligible.

- School Attendance:

- School-age children in the family must be attending school, and states can require teens without a high school diploma or GED to attend training or education as a condition of receiving TANF.

- Drug Testing:

- Some states require applicants to undergo drug testing.

- Residency:

- Applicants must be residents of the state where they are applying. Again, it’s crucial to understand that specific eligibility criteria and requirements can vary significantly from state to state.

Those interested in TANF should check their state’s guidelines or consult with a local social services office.

Scenario 0 – TANF (Non-Tribal) – Current State with HL7 FHIR Patient Focus Only:

Scenario: The Case of Maria Rodriguez

Maria Rodriguez is a single mother of three children living in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Recently laid off from her job due to economic downturns, Maria finds herself navigating a myriad of challenges. Besides ensuring her children’s education and well-being, Maria has health complications due to diabetes. Given her circumstances, Maria decides to apply for TANF to secure financial assistance for her family.

The Medical Interactions: When Maria visits the local clinic for her diabetes checkup, she’s registered as a “Patient” in the healthcare system. Her medical data, including her diabetic status, medications, and recent tests, are stored linked to her Patient resource.

The Social Interactions: As Maria starts the TANF application process, the social service agency needs to understand her broader context. This includes her family situation, number of dependents, employment status, and more. In an ideal world, they would access a comprehensive “Person” record that amalgamates Maria’s social and medical data.

However, because the HL7 FHIR framework is largely patient-centric, there is no straightforward way to link her medical data (stored under Patient) with her broader social profile.

The Gap and Its Implications: As Maria’s application proceeds, the TANF agency might need medical verification to support specific claims, such as potential added benefits due to her diabetic condition. Given the separation between Maria’s “Patient” and “Person” records, the agency has to initiate a cumbersome, manual verification process, causing delays and additional stress for Maria. Meanwhile, her healthcare provider remains largely unaware of her socio-economic challenges, which play a crucial role in her overall well-being and health.

The System’s Shortfall: As the TANF agency and healthcare provider operate in their silos, opportunities to provide holistic support to Maria are missing. For instance, she might benefit from a coordinated approach where her TANF support includes tailored health interventions or where her healthcare provider offers resources mindful of her socio-economic challenges.

In this scenario, the distinction between Patient and Person within the HL7 FHIR framework creates barriers to efficient and holistic service delivery. An integrated “Person-centric” approach, where Maria’s social and medical data coalesce, would foster better outcomes for individuals like her navigating both healthcare and social service systems.

Scenario 1 – TANF:

Use Case: Leveraging FHIR for ACF/TANF Eligibility

Actors:

- Linda Torres: A single mother of two children, ages 3 and 7. She recently lost her job due to company downsizing and is struggling to make ends meet.

- Ethan Moore: A social worker at a local community center who specializes in assisting families in need.

- Health-Connect System: An integrated Electronic Health Record (EHR) system enhanced with FHIR capabilities for SDOH.

Story:

Linda has been out of work for three months. Her savings are dwindling, and she’s concerned about providing for her children. She’s heard of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program but isn’t sure if she qualifies.

She visits the local community center and meets Ethan. He informs her of the TANF eligibility requirements:

- US citizenship or eligible non-citizen status.

- Low or very low income.

- Children under age 18 (or under age 19 if they are a full-time student in high school or a GED program).

- Proof of pregnancy (if applicable).

- Cooperation with child support services (if applicable).

- Participation in work or training activities (with certain exceptions).

Ethan then uses Health-Connect to input Linda’s details. The system, now enhanced to capture and interpret SDOH data via FHIR, flags several key points:

- Linda’s recent unemployment (based on data sharing with the unemployment agency).

- Her children’s ages and health requirements.

- The family’s recent financial struggles, including missed utility bills.

Health-Connect, with its integrated SDOH features, instantly assesses Linda’s circumstances and recognizes her need for additional support, potentially making her eligible for TANF. Ethan gets an instant alert about this potential eligibility, which helps streamline the process.

Enhancing FHIR’s Role:

Instead of Linda navigating the confusing paperwork and waiting for days or weeks for a response, the enhanced FHIR capabilities in Health-Connect allow Ethan to instantly understand her needs. By integrating SDOH data, the system paints a fuller picture of Linda’s situation, making it easier for social workers like Ethan to provide appropriate aid swiftly.

Conclusion:

Linda’s case illustrates the transformative power of integrating SDOH with FHIR. By streamlining the eligibility process and offering real-time insights into the lives of individuals, FHIR’s capabilities can ensure that those in need receive timely assistance, leading to better health and social outcomes.

Scenario 2 – TANF:

Narrative: Emma’s Journey Towards Stability with TANF

Emma, a 28-year-old woman living in urban Atlanta, is striving to rebuild her life after escaping a tumultuous relationship. With her three-year-old daughter, Mia, in tow, she moves into her sister’s two-bedroom apartment, hopeful for a fresh start. But without immediate employment and savings rapidly depleting, Emma is confronted with the urgent need for financial assistance.

She hears about the TANF program from a friend who once benefited from it. However, the sea of paperwork, the unfamiliar jargon, and the uncertainty of eligibility criteria are overwhelming.

Emma seeks guidance from a nearby community center, where she learns about the TANF eligibility criteria:

- Family Composition: As a single mother with a dependent child, Emma meets the fundamental family criteria for TANF.

- Income Limitations: Emma’s current lack of employment and minimal savings mean she falls within the state’s income and asset limitations for TANF assistance.

- Work Requirements: To continue receiving TANF benefits, Emma would have to participate in work or job training for a certain number of hours each week. The community center connects her with local job training programs tailored to her skills.

- Duration: The benefits would last up to a maximum of 48 months (this duration can vary by state), but Emma is optimistic about finding stable employment before reaching that limit.

- Child Support Cooperation: Since Emma’s circumstances involve leaving an abusive relationship, she might be exempt from pursuing child support or may need to make specific arrangements to ensure her safety.

With the center’s assistance, Emma submits her TANF application, attaching all necessary documents. While waiting for approval, she joins a job training program in the healthcare sector, seeing it as a growing industry with job security.

The Role of Enhanced FHIR in Emma’s Path:

Emma’s engagement with the TANF program provides a wealth of data that, when integrated into the healthcare system using FHIR standards, offers holistic care approaches. For instance, when Emma takes Mia for a pediatrician visit, the enhanced FHIR system could alert the doctor about their recent socioeconomic changes, leading to potential stressors for Mia.

Similarly, as Emma gets a job after her training and eventually moves out of TANF support, this positive shift in her economic status can be noted in her health records. This offers her healthcare provider a comprehensive view of Emma’s life, allowing them to provide more targeted and effective care. Moreover, health practitioners can identify and address any health issues that might arise from socio-economic stressors, ensuring both Emma and Mia receive the care and support they need.

This narrative strives to capture the complexities of navigating TANF while also emphasizing the potential of integrating such data with healthcare systems using FHIR standards.

Scenario 3 – Tribal TANF:

Tribal TANF is a version of the federal TANF program that allows American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes to run their own TANF programs to best serve their communities’ unique needs.

The requirements and benefits for Tribal TANF can differ from regular TANF programs because tribes can set their own guidelines.

Narrative: The Journey of Lila and Her Family to Tribal TANF Support

Lila, a single mother of two children, Nayeli (aged 10) and Takoda (aged 14), lives on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Lila recently lost her job at a local arts and crafts store, which had to close due to economic difficulties. The loss of her job has strained their financial situation, and Lila struggles to meet the family’s basic needs.

As a member of the Oglala Lakota tribe, Lila has heard of the Tribal TANF program specifically tailored for their community’s members. She considers applying, but she’s unsure of the eligibility criteria and process.

Upon consulting with a Tribal elder and community liaison, Lila learns the following:

- Tribal Connection: As members of a recognized tribe and residents of the reservation, Lila and her children are eligible to apply for Tribal TANF. Each tribe may have specific criteria regarding tribal membership or affiliation.

- Income and Asset Considerations: Like the standard TANF program, there are income and asset thresholds. However, given Lila’s recent job loss and her limited savings, she meets the criteria.

- Cultural Work Requirements: While work requirements exist, the Tribal TANF program often integrates cultural and community elements. Lila can participate in local tribal cultural events, teachings, or community services to meet these requirements. This integration ensures that she stays connected with her heritage while acquiring new skills or supporting her community.

- Support for Indigenous Practices: Nayeli and Takoda’s involvement in traditional dances and ceremonies can be considered under the program’s educational and cultural enrichment activities.

- Duration of Assistance: Tribal TANF programs might have their own set duration for assistance, but Lila learns that she can receive support for up to 60 months. Special considerations or extensions may be provided for families facing severe hardships.

- Customized Assistance: Tribal TANF can offer more than just monetary aid. There could be additional support in the form of counseling, job training specific to tribal industries, and childcare services during community events.

Lila decides to apply and is guided through the process by the tribal social services office. They help her gather necessary documents and ensure her application is complete.

Enhancing FHIR to Address Lila’s Journey:

By integrating Tribal TANF data with the FHIR standard for Social Services and Social Determinants of Health (SDOH), a more holistic view of Lila’s health and well-being can be achieved.

When Lila visits a healthcare provider, they can access her Tribal TANF data through enhanced FHIR standards. This provides a broader context to her health status and needs. The provider learns about the economic strains Lila’s family is facing and can offer resources or referrals that address not just medical but socio-economic needs.

Furthermore, as Lila participates in cultural events and community services to fulfill her work requirements, this data can be shared with other social services, ensuring she receives comprehensive support. For example, if Lila decides to enroll in a job training program provided by the tribe, her healthcare provider, through the enhanced FHIR system, can be aware of this positive change in her life, which might have direct implications for her mental and physical health.

This narrative presents a potential journey through Tribal TANF while also showcasing the importance of integrating such data into broader healthcare systems using FHIR and SDOH standards.

Scenario 4 – Tribal TANF:

Tribal TANF Model Use Case: Towards a ‘Whole Person Care’ Approach

Deep within the confines of a tribal reservation, life thrives on a delicate blend of modernity and traditions. Maya, with her vivacious spirit, grew up amidst age-old stories, sacred rituals, and the protective embrace of the mountains. The city’s bright lights lured her for a few years during college, but the call of the land was too strong. Now, a single mother of two, Maya finds herself navigating the intricacies of both worlds - her tribal heritage and the challenges of raising children in a rapidly modernizing landscape.

Things took a turn when Maya’s mother, Aria, fell ill, and Maya lost her job. As medical bills stacked up and daily expenses became harder to meet, Maya decided to apply for TANF assistance to ensure her family didn’t face even tougher times. Here, the intricacies of data interoperability played a crucial role.

Traditionally, medical systems utilize the HL7 FHIR’s Patient Resource as their primary focus, which, while effective for strictly medical scenarios, fails to capture the broader human experience. When Maya interacted with the healthcare system, her data was stored in this Patient Resource. Yet, Maya’s life, particularly as part of the tribal community and as a TANF applicant, involved multiple roles and experiences that were much broader than just her health information.

Maya’s TANF eligibility wasn’t just about her financial status but also tied to her cultural background, responsibilities as a caregiver, her children’s school statuses, and so on. In the FHIR ecosystem, the Patient Resource couldn’t holistically represent Maya. The Person Resource in FHIR, which accounts for a broader definition of an individual beyond just their medical data, would be more suitable.

As Maya began her TANF application, the process hit several roadblocks. The tribal TANF program, while taking into account her financial constraints, also had specific requirements that considered her tribal status, her participation in tribal events, and her efforts in maintaining tribal traditions. When the TANF system tried to retrieve her medical data to understand her mother’s health status and her responsibilities as a caregiver, it clashed with the existing Patient-centric FHIR model.

Maya found herself caught in a whirlpool of paperwork, with the TANF system failing to retrieve comprehensive information about her. The “broken” Patient/Person model in FHIR meant systems couldn’t seamlessly communicate, leading to significant gaps in understanding Maya’s life circumstances.

This inefficiency highlighted the need for a shift in perspective in data standards like FHIR. Rather than pigeonholing individuals as mere ‘patients,’ systems should first recognize them as ‘persons’ with multifaceted lives, and only then as ‘patients’ when interacting with healthcare settings. A “Whole Person Care” approach using an enhanced Person Resource would streamline Maya’s interactions, reducing redundancies, ensuring she receives the assistance she needs, and ultimately fostering a more holistic and human-centric service delivery.

Actors:

- Maya: A 28-year-old single mother of three children aged 2, 5, and 7.

- Lucas: Maya’s 7-year-old son, who has a chronic respiratory condition.

- Tribal TANF Caseworker: Handles Maya’s application and periodic reviews.

- Community Health Worker: Coordinates healthcare needs within the tribal community.

- TANF System: The digital infrastructure handling TANF applications and benefits.

- Healthcare System: The electronic health records (EHR) system of the local tribal clinic.

Scenario:

- Maya’s Plight:

- As winter approached, Maya grew increasingly worried about Lucas’s health and the family’s financial stability. Remembering whispers about the Tribal TANF program, she decided to seek assistance.

- Application Process:

- At the tribal office, Maya met the Tribal TANF Caseworker, recounting her struggles, emphasizing Lucas’s health condition.

- The caseworker began Maya’s application, but the TANF System, isolated from other databases, required extensive details about Maya’s financial, family, and housing situations.

- Healthcare Integration Challenges:

- Noticing Lucas’s condition, the caseworker wished for a seamless integration between TANF and Healthcare Systems, allowing them to access Lucas’s medical history and understand its influence on the family’s financial needs.

- The current systems, however, prioritized Lucas as a ‘Patient,’ disregarding the family’s holistic social circumstances.

- Whole Person Care Dilemma:

- The Community Health Worker noted Lucas’s specialized care needs outside the tribal community. Yet, the systems fragmentation made it tough to incorporate this into Maya’s TANF application.

- Maya felt lost, navigating different platforms and repeatedly providing the same details.

- Re-imagining the Process:

- A ‘Person’-centric model would have showcased Lucas’s comprehensive profile, linking his educational, housing, and healthcare needs. This could expedite the TANF process and provide targeted assistance.

- Impact & Resolution:

- Maya’s emotional and financial stress increased due to system inefficiencies, risking Lucas’s health.

- Recognizing these challenges, the tribal community pushed for a ‘Person’-centric approach, paving the way for holistic care and streamlined social services.

Incorporating background and story elements into this use case paints a vivid picture of Maya’s struggles, underscoring the pressing need to transition from a strictly ‘Patient’ centric model to a more comprehensive ‘Person’-centric approach.

Enhancing FHIR to Address Maya’s Journey

The complexities of Maya’s journey, with its intersections of healthcare, social determinants of health, tribal affiliations, and familial responsibilities, underscore the limitations of the current HL7 FHIR model. To truly serve individuals like Maya, FHIR needs enhancements that prioritize holistic care.

- Unified Person-Patient Model: Central to this is the need to rethink the Patient and Person resources in FHIR. Instead of seeing them as separate, we should consider a unified approach. For instance, a ‘Whole Person Resource’ could be introduced to FHIR, encapsulating every aspect of an individual’s life.

- Contextual Data Integration: Maya’s tribal affiliations, her responsibilities towards her mother Aria, her children’s educational background, and her TANF interactions all require different datasets. FHIR resources should be flexible enough to capture these nuances, possibly through extensible fields that allow data from diverse sources to be integrated contextually.

- Interoperable Communication Channels: FHIR’s communication resources should be expanded to allow seamless interaction between healthcare, social care, educational institutions, and tribal organizations. This way, when Maya seeks TANF assistance, there’s a holistic understanding of her circumstances, without the need for redundant paperwork or repeated inquiries.

Outcomes

After implementing an enhanced FHIR model:

- Maya’s interactions with the TANF system become streamlined. The need for repetitive documentation diminishes as the system can fetch all relevant information seamlessly.

- The TANF system, understanding Maya’s multifaceted background, is able to provide her with assistance tailored to her unique needs. This not only includes financial aid but also resources related to tribal health practices, assistance for Aria’s medical care, and educational support for her children.

- The success story of Maya becomes a beacon for similar implementations across the nation. Tribal communities, in particular, find their interactions with national assistance programs to be more tailored, understanding, and efficient.

- At a systemic level, healthcare and social care ecosystems become more integrated. Individuals are no longer siloed into restrictive categories but are seen holistically, fostering better care outcomes and more human-centric service delivery.

In this new paradigm, Maya’s story isn’t just one of individual triumph but becomes emblematic of a systemic shift towards true “Whole Person Care”.

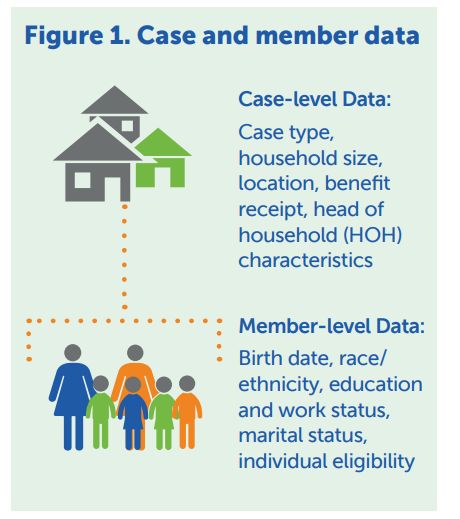

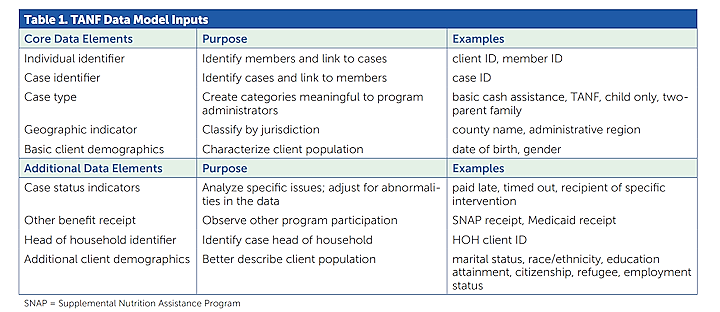

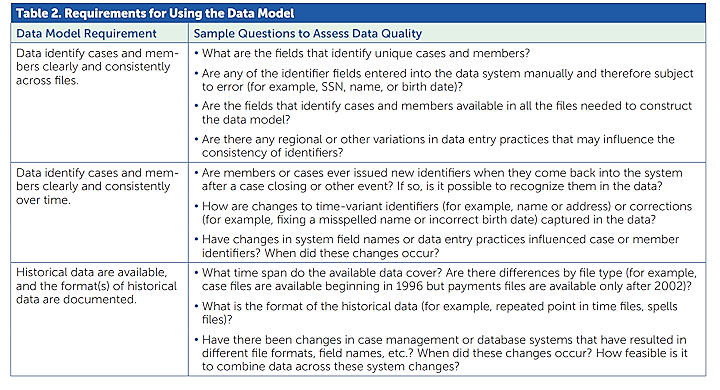

Existing Data Models from the Family Self-Sufficiency Data Center (FSSDC):

The Family Self-Sufficiency Data Center (FSSDC) is funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, to facilitate use of administrative data by researchers and administrators to improve understanding of, and identify methods for increasing, family well-being. The FSSDC has worked with several state Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) offices to improve the accessibility and usefulness of TANF administrative data.

*Sources (for Data Model/Images Section):

Wiegand, E., Goerge, R., & Gjertson, L. (2017). Creating a Data Model to Analyze TANF Caseloads. Family Self-Sufficiency Data Center & THE CONSORTIUM: Stimulating Self-Sufficiency & Stability Scholarship. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago; University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy.