Validated Healthcare Directory, published by HL7 International / Patient Administration. This guide is not an authorized publication; it is the continuous build for version 1.0.0 built by the FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) CI Build. This version is based on the current content of https://github.com/HL7/VhDir/ and changes regularly. See the Directory of published versions

| Page standards status: Informative |

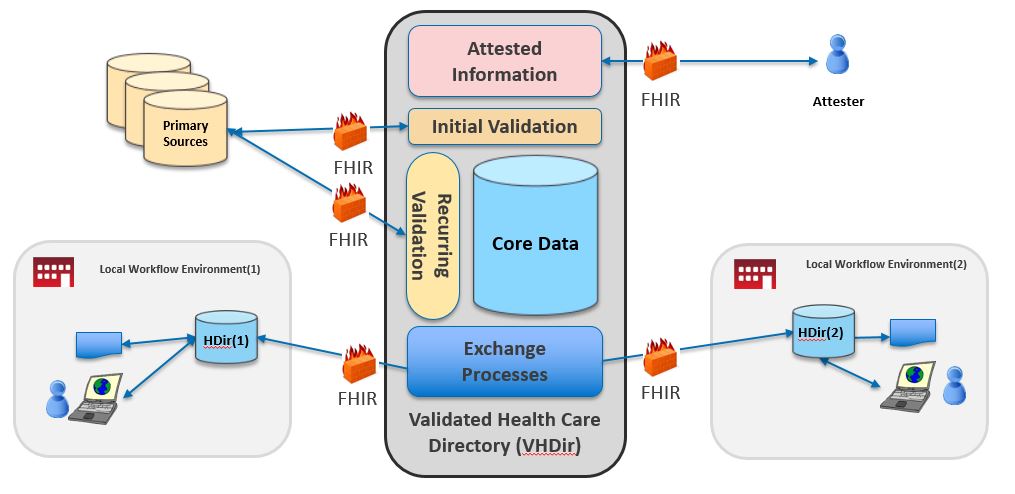

This diagram depicts the high-level conceptual design of a central source of validated healthcare directory data.

In this diagram, RESTful FHIR APIs facilitate the movement data into and out of a validated healthcare directory (VHDir) at different points, including:

Attestation describes the process by which authorized entities submit information about themselves, their roles, their relationships, etc. for inclusion in a healthcare directory.

Guidance in this section is primarily intended to describe expectations for implementers using a FHIR API to manage attestation. An implementer’s unique implementation context, including local business needs, applicable laws/regulations/policies, usability considerations, etc. will determine an implementer’s approach to many of the attestation considerations described in this section. As we do not anticipate every implementer will use the same approach to attestation, we have not provided a set of attestation profiles or defined an attestation API. Implementers SHALL make any attestation requirements, including but not limited to profiles and/or API documentation, available to any stakeholders involved in the attestation process.

We acknowledge that implementers may use processes other than a FHIR API, such as paper-based forms, to obtain attested data. Such processes are considered out of scope for this guide.

This guide covers multiple attestation scenarios:

Each of these scenarios may encompass different sets of “permitted” data. For example, an individual provider attesting to her own information may not have the right to also attest to information about an organization she works for. These “rights” are assigned by each implementation of a validated healthcare directory, and can help prevent the submission of duplicate records. In general:

Additionally, implementers may set requirements for the minimum amount of data different groups of stakeholders must attest to. For example, a US implementation might require all licensed providers to attest to their National Provider Identifier (NPI). In general, implementers might specify different minimum attestation requirements across three classes of stakeholders:

We expect stakeholders will typically use a SMART on FHIR application to help attesters manage the attestation process (i.e. to submit attested data in the form of FHIR resources via a RESTful API). Such an application may be offered by an entity maintaining a validated healthcare directory or owned by the stakeholder(s) submitting attested data.

Before accepting attested data, a validated healthcare directory should have policies to ensure:

Once these preconditions have been met, a typical attestation workflow might involve:

The FHIR specification describes multiple approaches for managing interactions over an API, including:

This implementation guide is not prescriptive about which approach(es) a validated healthcare directory should use to manage attestation. However, as any attestation will likely involve the submission of multiple FHIR resources representing information about one or more attesters, transaction Bundles can alleviate the need for more complex logic to manage referential integrity in attested information.

Implementations relying on individual API interactions or batch Bundles may have to specify an “order of operations” to ensure attested data can be successfully submitted to the validated healthcare directory server. For example, as a general guideline, resources may need to be submitted in the order of:

Depending on the context of implementation, entities maintaining a validated healthcare directory may have to manage record collision or duplication (i.e. multiple attesters attempting to simultaneously submit updates to the same record, or multiple attesters attempting to attest about the same set of information).

The FHIR specification provides some guidance on managing collisions using a combination of the ETag and If-Match header in an HTTP interaction. We recommend validated healthcare directory implementers use this approach.

To manage duplicate records, we generally recommend that validated healthcare directory implementers define a robust validation process with policies for identifying and resolving duplicates. Any additional technical capabilities are beyond the scope of this implementation guide.

Validation is critical for ensuring that users of a healthcare directory can rely upon the data in the directory. Validation can refer to separate but related processes: validation of FHIR resources (e.g. checking consistency w/data type, required elements are present, references to existing resources are correct, codes are from appropriate value set etc.), and validation of data against a primary source (e.g. verifying an address using Post Office records). This section describes the latter.

Implementers will typically determine how primary source validation occurs operationally, based in part on the capabilities of the primary sources used for validation. For example, a primary source may already offer a mechanism like an API for validating content against its records. In other cases, an implementer may want to define an API that the primary source can access to push and/or pull content related to validation. Implementers may also consider less technical approaches, such as manual validation, or more stringent requirements, such as mailing a postcard to confirm an address.

Certain types of data may have different validation requirements. For example, validating a relationship might require confirmation from each stakeholder participating in the relationship. Some data may have to be validated more frequently (e.g. license status), while other data can be validated once (e.g. education history) or not at all (e.g. a provider’s spoken language proficiency).

As with attestation, we expect VHDir implementers may use different approaches to validation. Therefore, we have not defined specific validation requirements or a validation API. Implementers SHALL make any validation requirements, including but not limited to profiles and/or API documentation, available to any stakeholders involved in the validation process.

This implementation guide includes a Validation profile for the VerificationResult resource for representing information about validation. The VerificationResult resource includes a number of data elements designed to record information pertaining to the validation processes defined by implementers, as well as the outcome of validation for a specific data element/set of elements/resource. The Validation profile includes data elements describing:

Validation may occur on the total contents of a resource, a collection of elements in a resource, or a single element. Any entity with access to a data element in a validated healthcare directory SHALL also have access to any validation information pertaining to that element.

The primary focus of this implementation guide is a RESTful API for obtaining data from a Validated Healthcare Directory. The exchange API only supports a one-directional flow of information from a Validated Healthcare Directory into local environments (i.e. HTTP GETs).

Any Validated Healthcare Directory IG conformant implementation:

In profiles, the "Must Support" flag indicates if data exists for the specific property, then it must be represented as defined in the VHDir IG. If the element is not available from a system, this is not required, and may be ommitted.

Conceptually, this guide was written to describe the flow of information from a central source of validated healthcare directory data to local workflow environments. We envisioned a national VHDir which functioned as a “source of truth” for a broad set of provider data available to support local business needs and use cases. A local environment could readily obtain all or a subset of the data it needed from the national VHDir and have confidence that the information was accurate. If necessary, a local environment could supplement VHDir data with additional data sourced and/or maintained locally. For example, a local environment doing provider credentialing might rely on a national VHDir for demographic information about a provider (e.g. name, address, educational history, license information, etc.), but also ask the provider for supplementary information such as their work history, liability insurance coverage, or military experience. Likewise, we envisioned that a VHDir would primarily share information with other systems, rather than individual end users or the general public.

The content of this guide, however, does not preclude it from being implemented for smaller “local” directories, or accessed by the general public. Generally, conformance requirements throughout the guide are less tightly constrained so as to support a wider variety of possible implementations. We did not want to set strict requirements about the overall design, technical architecture, capabilities, etc. of a Validated Healthcare Directory that might prevent adoption of this standard. For example, although we would expect a national directory to gather and share information about healthcare provider insurance networks and health plans, implementations are not required to do so to be considered conformant.

We acknowledge that this decision has the potential to impact the interoperability of healthcare directory data and lead to variable implementations. However, we believe this risk is balanced by the potential for greater standardization of healthcare directory data enabled by this IG. We expect jurisdictions (e.g. countries) to further constrain this IG to meet their unique needs and publish the results openly and transparently.

Especially with larger-scale implementations, healthcare directories may contain a large amount of data that will not be relevant to all use cases or local needs. Therefore, the exchange API defines a number of search parameters to enable users to express the scope of a subset of data they care to access. For example, implementations are required to support searches for Organizations based on address, endpoint, identifier, name/alias, and relationship to a parent organization. In general, parameters for selecting resources based on a business identifier, status, type, or relationship (i.e. reference) are required for all implementations. Most parameters may be used in combination with other parameters and support more “advanced” capabilities like modifiers and chains.

The VHDir API currently supports one method for accessing directory data, a real-time pull. However, stakeholders may need other capabilities to support different business needs. For instance, stakeholders may need access to large amounts of VHDir data in a single session to either initially seed or refresh their local data repositories. Depending on the scope of data a stakeholder is trying to access, a real-time pull may not be the most effective method for acquiring large data sets. The FHIR specification provides support for asynchronous interactions, which may be necessary for implementers to facilitate processing of large amounts of data.

VHDir implementations should also consider providing capabilities for users to subscribe to receive updates about the data they care about. A subscribe/publish model can help alleviate the need for stakeholders to periodically query a VHDir for new data and/or changes to data they have already obtained.

Likewise, implementers should consider supporting a mechanism to push urgent updates or changes to data that may impact business decisions or safety. For example, a VHDir might push updates about a practitioner’s record if their medical license is suspended or revoked.

We envision VHDir as a public or semi-public utility. Stakeholders who agree to abide by the VHDir’s policies and procedures, signed a data use agreement, etc. would generally have access to VHDir data (note: we consider specific operational policies and legal agreements out of scope for this IG). However, in some implementations, a VHDir may include sensitive data that is not publicly accessible or accessible to every VHDir stakeholder. For example, an implementer might not want to make data about military personnel, emergency responders/volunteers, or domestic violence shelters available to everyone with access to a VHDir, or to users in a local environment who have access to data obtained from a VHDir.

We expect that a VHDir’s operational policies and legal agreements will clearly delineate which data stakeholders can access, and if necessary, require stakeholders to protect the privacy/confidentiality of sensitive information in downstream local environments. As such, we have included a Restriction profile based on the Consent resource to convey any restrictions associated with a data element, collection of elements, or resource obtained from a VHDir.

Although FHIR resources define discrete business objects, related resources may have similar data elements. For example, the HealthcareService, PractitionerRole, and Location resources all include data elements describing availability. In some circumstances, values in these common data elements may not align across resources, potentially creating ambiguity. For example, in this IG, a Location resource might indicate that the location no longer accepts patients. However, a PractitionerRole resource for a provider working at the location might indicate that the provider is accepting patients (e.g., by referral only). In some cases, these inconsistencies are valid representations of the complexities of healthcare systems. In others, data might have been entered in error, outdated, or otherwise inaccurate.

The FHIR specification does not provide guidance on managing common elements across resources to reduce redundancy or ambiguity. Likewise, this implementation guide does not provide additional guidance. Implementations should consider further constraining profiles, creating invariants, or requiring data sources (e.g. attesters) to contribute data in a consistent format. Some resources include elements for describing exceptions, such as the availabilityExceptions field on HealthcareService, Location, and PractitionerRole. Additionally, validation processes may help discover and address inconsistencies across resources.