Clinical Practice Guidelines, published by HL7 International / Clinical Decision Support. This guide is not an authorized publication; it is the continuous build for version 2.0.0 built by the FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) CI Build. This version is based on the current content of https://github.com/HL7/cqf-recommendations/ and changes regularly. See the Directory of published versions

Covered in this section:

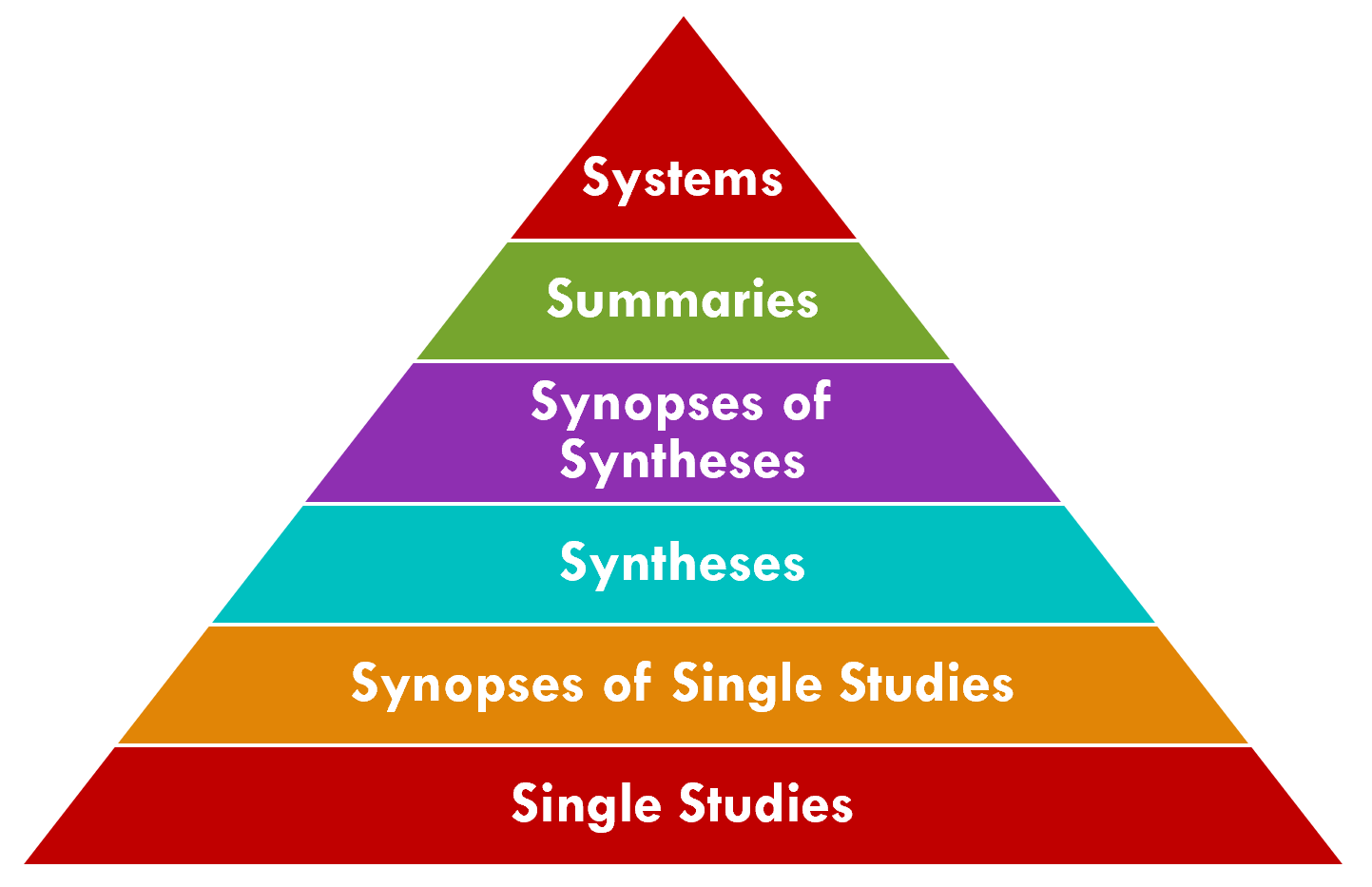

The 6S Evidence Pyramid is another framing on the quality or validity of the evidence that may be of particular interest to the CPG-IG (implementation guide)1. A detailed explanation of the 6S Pyramid is beyond the scope of this document, however we will explain a few key points as they pertain to the guideline development process, in particular the quality of evidence as well as how the CPG actually enables the ascent to the peak.

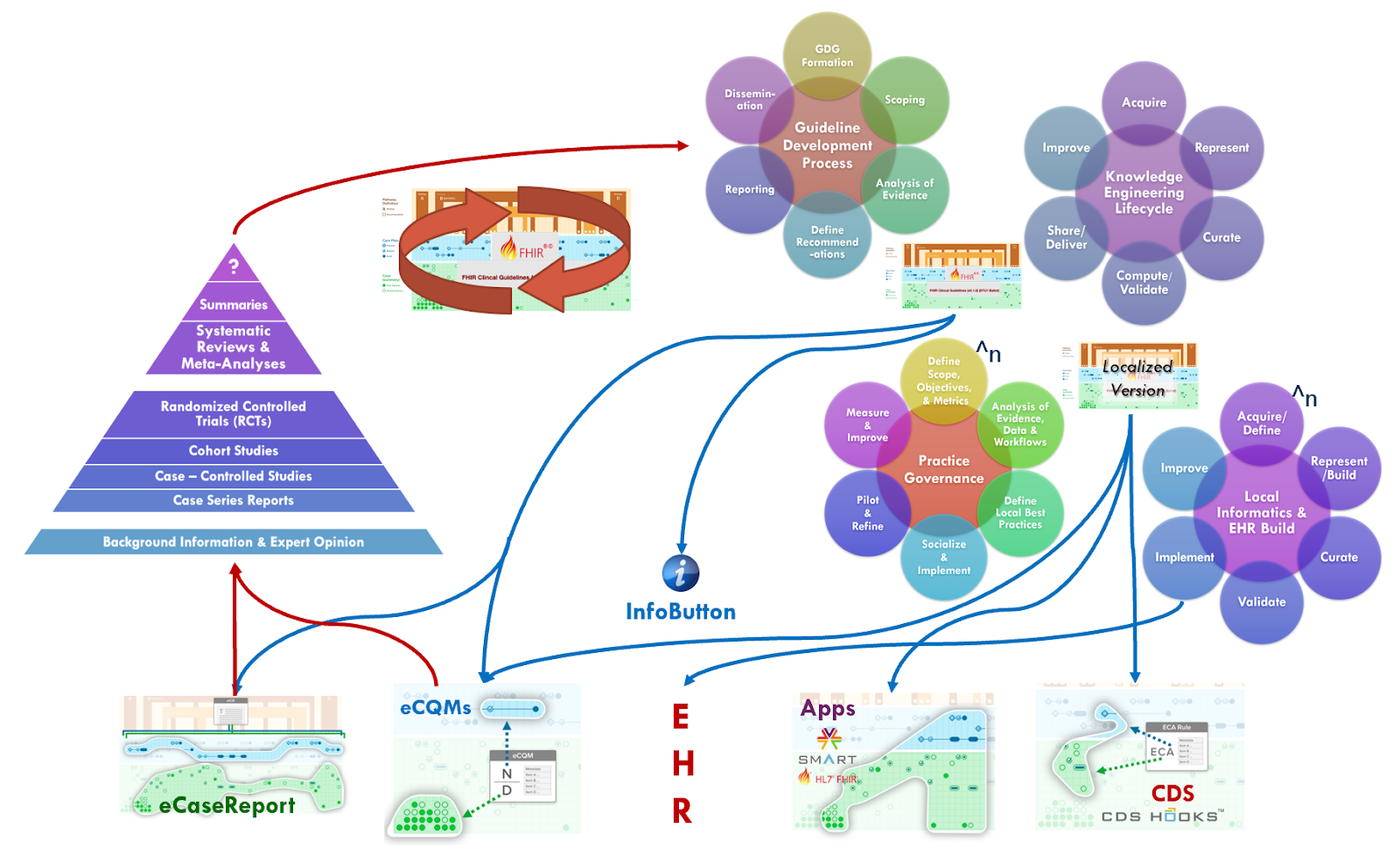

The CPG has the potential to address the "systems" level (i.e., peak of the pyramid), which is described as: “Integrating information from the lower levels of the hierarchy with individual patient records, systems represent the ideal source of evidence for clinical decision-making.” (ref). The CPG affords the ability to directly insert guideline recommendations into electronic health records (EHRs) and clinical information systems based on reasoning over real-world, patient-specific clinical data to be considered directly in the context of clinical and shared decision-making.

Furthermore, profiles like the CPGeCaseReport, inclusive of all guideline-scoped patient information (CPGCaseFeatures), patient-specific recommendations (CPGProposals) and their respective responses (as CPGCaseFeatures), patient-level quality measures (CPGMetrics), and the corpus of evidence available and used at the time of recommendation (CPGEvidence), allows the informational means to further provide real-world evidence of the usage and effectiveness of such recommendations. This response and timing from recommendation to when the clinician takes action on the recommendation (e.g., order, prescribe, schedule) and their fulfillments (e.g., administrations, results, performances) as well as the patient-specific context for each key event providing a view into critically valuable information about guideline usage that itself may become evidence for various research studies that yield their own high quality evidence.

Intermediate and ultimate outcomes at the patient-level, including those reported by the patient, could be collected by the CPGeCaseReport. Lastly, CPGCaseFeatures may include ‘snippets’ of narrative from clinical impressions related to the response and/or other contextualization of a patient-specific guideline recommendation or decision. This kind of narrative explanation for the clinicians' decision-making process or assessment may provide significant insight into the impact and effectiveness of various characteristics of the recommendation and/or CPG-derived decision-support interventions.

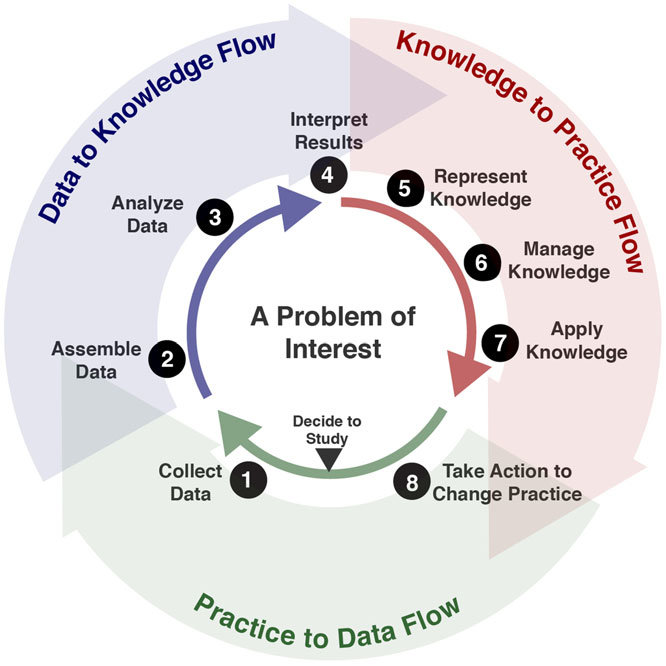

Altogether, the CPG’s have the ability to deliver the lower levels of evidence through the guideline development process and its referenced evidence directly into patient care and related healthcare delivery processes as well as provide individual, aggregated, and potentially continuous feedback loops on both the patient specific recommendations (CPGProposals) and the resulting care delivered and numerous relevant real-world data elements scoped to or by the CPG. This continuous feedback loop is often referred to as the “Learning Health System”3

Clearly there are many benefits to enable such a “peak of the pyramid” approach to tightly integrating guideline-directed care and cycling the “Learning Health System” for any condition and at any point in time. However, perhaps none more so than a situation where there is a public health emergency with significant mortality and where there is poor quality or low level of evidence for how to best address the novel contagion as well as the clinicopathophysiological (disease processes and manifestations) that it causes. There are several clear benefits and advantages to such an approach including the use of other techniques, disciplines, and approaches described elsewhere in this implementation guide. We will address a few of them here and provide references to where else in this document related content can be found. Many of the approaches, capabilities, best practices, tools, and techniques described in this implementation guide are certainly as, if not even more, relevant to these situations.

One of the first priorities in a situation where evidence and best practice is significantly lacking is to establish a means to start discovering evidence for best practices. In addition to typical public health incident case report information (confirmatory labs and demographics), patient and population-level information about the clinicopathophysiological nature of the human body’s disease or disordered response to the contagion as is critical to have early on. Likewise, information around the likely interventions for this disease or disordered responses to the contagion together with information on response to treatment as well as intermediate- and end-outcomes is critically important to discover the effectiveness, timing, and contextualizing factors (e.g. other patient-level information) for these interventions. One of the earliest components of a CPG to be identified and mature, and the set of required data elements (CPGCaseFeatures) and key inferences (derived or inferred CPGCaseFeatures) that are inclusive of requests (orders, prescriptions, scheduled procedures, etc.) and various clinical data elements. A CPG with few or even no recommendations may be developed using the approaches in this implementation guide with the primary purpose of collecting relevant data (see section on eCaseReport).

Evidence of and for best practice may begin to emerge through such data using various means including approaches described briefly and a high level and other sections of this implementation guide (see section on Knowledge Acquisition and in particular: Knowledge Discovery; Hybrid Approaches; and In Collaboration with Knowledge Implementers)

As evidence begins to emerge through such data through various means including using approaches described briefly and a high level and other sections of this implementation guide (see section on Knowledge Acquisition and in particular: Knowledge Discovery; Hybrid Approaches; and In Collaboration with Knowledge Implementers), best practice guidance (and/or guidelines) can then be rapidly developed, delivered, and implemented using other approaches described in this document (see sections on Agile CPG Development Process and on Knowledge Implementation).

Alternatively, with a lack of high quality evidence and available evidence-based best practice guidance, some of the earliest (though low quality) best practices may be actively discovered firsthand on the front lines and reported as case studies or series studies (though low in evidence quality). However, such guidance in certain situations may be at least informative to frontline providers, and inform additional relevant data collection on related clinicopathological processes, interventions, and response (including outcomes) thereto as described above (see section on eCaseReport).

In either scenario described above- rapid discovery of best practice, or rapid dissemination of practice guidance, the ascent to the peak of the pyramid through a rapid-cycle Learning Health System can be initiated. Whether it be data-to-evidence, or practice-to-data, the full closed loop knowledge discovery-to-delivery lifecycle need not be dependent on evidence-to-practice as is the usual case in the guideline development process and the supporting Agile CPG development process. There are numerous feedback, and feedforward, loops described in this implementation guide that can facilitate continuous learning as well as evidence updates. (see Agile CPG Development Process and eCaseReport). This cycle may be thought of as either: Data-to-Evidence-to-Knowledge-to-Practice; or Guidance-to-Practice-to-Data-to-Evidence-to-Knowledge-to-Practice

1: DiCenso A, Bayley L, Haynes RB. Accessing preappraised evidence: fine-tuning the 5S model into a 6S model. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:JC3–2. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-6-200909150-02002

2: Khangura, S., Konnyu, K., Cushman, R., Grimshaw, J., & Moher, D. (2012). Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Systematic reviews, 1, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-10

3: https://www.ahrq.gov/learning-health-systems/about.html

4: Flynn, Allen & Friedman, Charles & Boisvert, Peter & Landis‐Lewis, Zachary & Lagoze, Carl. (2018). The Knowledge Object Reference Ontology (KORO): A formalism to support management and sharing of computable biomedical knowledge for learning health systems. Learning Health Systems. 2. 10.1002/lrh2.10054.